Neuroinflammation in bipolar disorders

Abstract

Recent literature based on peripheral immunity findings speculated that neuroinflammation, with its connection to microglial activation, is linked to bipolar disorder. The endorsement of the neuroinflammatory hypotheses of bipolar disorder requires the demonstration of causality, which requires longitudinal studies. We aimed to review the evidence for neuroinflammation as a pathogenic mechanism of bipolar disorder. We carried-out a hyper inclusive PubMed search using all appropriate neuroinflammation-related terms and crossed them with bipolar disorder-related terms. The search produced 310 articles and the number rose to 350 after adding articles from other search engines and reference lists. Twenty papers were included that appropriately tackled the issue of the presence (but not of its pathophysiological role) of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder. Of these, 15 were post-mortem and 5 were carried-out in living humans. Most articles were consistent with the presence of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder, but factors like treatment may mask it. All studies were cross-sectional, preventing causality to be inferred. Thus, no inference can be currently made about the role of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder, but a link is likely. The issue remains little investigated, despite an excess of reviews on this topic.

Keywords

Introduction

Among the former mood or affective disorders, bipolar disorder is the one that is most intriguing. Its heterogeneity is well-recognized. While traditionally subdivided into bipolar I and bipolar II according to whether there was a history of mania,[1] some scholars support the existence of more than 10 subtypes.[2] It is supposed to be pathophysiologically/neurobiologically continuous with other psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia according to Griesinger’s model of Einheitspsychose,[3] and with recurrent major depression.[4-6]

Mood disorders along with anxiety disorders are considered "stress disorders".[7] The organism responds to stress in an integrated manner, involving the cooperation among the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems,[8] and stress disorders are believed to be underpinned by derangements in this integration.[9]

Stress and inflammation

Inflammation is a process described since antiquity, meaning burning in both Greek (φλόγωσις) and Latin (inflammation), and characterized by swelling (tumor), redness (rubor), heating (calor), pain (dolor), and impaired function (functiolæsa). It is a general reaction to pathogens in a tissue involving an innate response of cells residing within that tissue. In the acute phase, the process entails the extravasation of immune cells, permeability changes in blood vessels, and the production of chemical mediators, including acute phase proteins, vasoactive amines, eicosanoids, bradykinin and other tachykinins, and chemical attractors. The nonspecific response usually leads to resolution and repair, with restitution to integrity. The inability to restore the previous healthy state may ensue in chronic inflammation, characterized by shifts from the main participating cells towards mononuclear (monocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma) cells and fibroblasts and from the main participating molecules towards interferon-γ, interleukins, growth factors, nitric oxide, and hydrolytic enzymes.[10]

The stress concept was developed from the work of Hans Selye,[11-12] who viewed the body in Cannon’s frame.[13] Stress, like inflammation, was proposed to be the body's response to "diverse nocuous agents",[11] a general adaptation syndrome characterised by an integrated neuroendocrine and immune response tending to restore homeostasis. Selye[12] showed that the response also involves the immune system, which constitutes another parallel with the inflammatory response. Currently, the stress response is considered to be evolutionary and likely to amplify an organism’s resistance to environmental stressors. Like inflammation, the inability of an organism to adequately address stress may lead to a stress disorder, which in psychiatry is represented by post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorders, and mood disorders such as depression.

In recent years, there has been an increasing recognition of altered immunological parameters in many psychiatric disorders, including depression, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorders, and schizophrenia.[14,15] The rationale is that chronic inflammation, by releasing cytokines, may set brain function into a “sickness mode”, thus causing psychiatric disorders. However, how this is carried-out is not explained, so it remains an interesting paradigm with no demonstration so far.

What do we intend by "neuroinflammation"?

Neuroinflammation is defined as inflammation of the central nervous system (CNS). It consists of increased glial activation, pro-inflammatory cytokine content, blood-brain-barrier permeability, and leucocyte extravasation. The process is believed to be driven by interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), a cytokine that has been found to be increased in neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis. IL-1β stimulates the IL-1 receptor/IL-1 accessory protein complex to increase glia NFkB-dependent transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-6, and interferons, as well as the neutrophil-recruiting chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL2. The whole process appears however to be mediated through stress,[16] which is a very general term, but it is essential to understand neuroinflammation as part of a whole in the pathophysiology of various disorders, and disease in general.

There has been evidence that neuroinflammation is reflected in changes in peripheral immunity,[17] but the reverse may not be true, hence, evidence of peripheral immunological alterations cannot be taken to indicate the presence of neuroinflammation. There is no consensus as to whether central and peripheral immunity are specular, and a recent study that adequately addressed the issue showed that brain immune markers were found to be independent from the peripheral activity of the immune system.[18]

Summarizing, stress may lead to the establishment of a chronic inflammatory reaction, which may occur in the brain in parallel to the periphery, thus setting brain function in a sickness mode that may substitute default activity and perpetuate the disorder. This does not explain the oscillatory mood activity. The presence of neuroinflammation in the brain in patients with bipolar disorder can help to answer whether neuroinflammation is a general way by which manic-depressive symptoms are produced. It is not sufficient evidence to demonstrate some of these symptoms in people with autoimmune neuroinflammation or other disorders showing both neuroinflammation and cognitive or mood alterations proper of bipolar disorder. Instead, convincing evidence requires the demonstration of neuroinflammation in a population of patients with bipolar disorders who have no other comorbidity. For this reason, we consider studies that point to the existence of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder only those studies investigating microglial activation or showing increased presence of neuroinflammatory markers in the human brain, in people with bipolar disorder compared to healthy or nonpsychiatric controls. These may be post-mortem studies or studies in living humans that involve the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or brain imaging.

Having this in mind, we aimed to review the evidence for neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder.

Our search strategy to investigate neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder

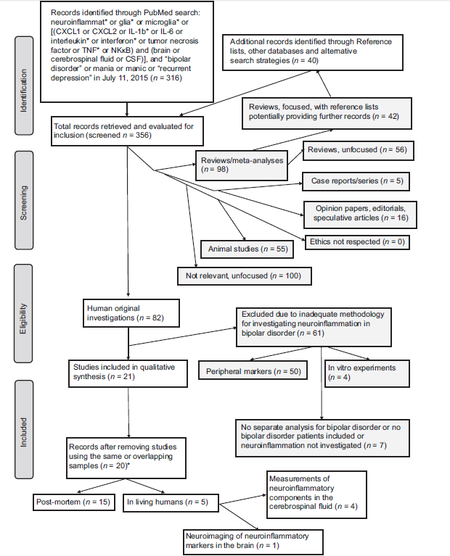

We performed a careful PubMed search using the following strategy: (neuroinflammation* or glia* or microglia* or [(CXCL1 or CXCL2 or IL-1b* or IL-6 or interleukin* or interferon* or tumor necrosis factor or TNF* or NKκB) and (brain or cerebrospinal fluid or CSF)] and (“bipolar disorder” or mania or manic or “recurrent depression”). There were no restrictions as to publication date or language. To be included, the paper had to be an original article and carried-out in humans. We did not restrict our search to human studies using the related PubMed function, because in our experience this practice does not exclude completely animal studies, but is likely to conceal some relevant human investigations instead. Hence, animal studies were subsequently excluded on the basis of evidence. Furthermore, we excluded reviews and meta-analyses, opinion/speculative papers, animal studies, case reports, as well as papers conducted without respect of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki Principles of Human Rights, reviews and meta-analyses, opinion/speculative papers, animal studies, as well as case reports. However, their references, especially those of reviews/meta-analyses were searched for possible further includible papers. This review followed the bureaucratic Prisma statement[19,20] when appropriate. We inverted the order recommended for screening, i.e. first exclude duplicates and then screen. We first classified studies according to their type, then excluded animal studies, reviews and studies of peripheral immunity, and included only human studies with data, including clinical and post-mortem, but not in vitro experiments on cell lines. We also excluded and classified as unfocused those post-mortem studies investigating glia in the brain without telling microglia from other types of glial cells. We excluded all non-peer reviewed literature, as it could constitute a source of bias. We considered as duplicates only studies that reported the same results in different published reports. When different studies by the same research group progressively report on increasingly larger samples and when the past used sample is used and accrued, we adopt the strategy to disregard the first appearing papers, including only the last study with the larger sample, provided its quality of evidence is high. Papers reporting on the same samples, but on different measures, were considered as different studies and included if appropriate. Contrary to the distinction made by the Prisma statement between records and full-text articles, we considered all papers emerging from our research as papers to obtain in full text and carefully searched for any data that conformed to our aims. Our experience is that you can never say if you only read the abstract, especially for not so recently published papers.

Contrariwise to what Prisma dictates, we did not label our review as "systematic" and did not attempt to carry-out a meta-analysis, both because the concepts of quantitative and qualitative syntheses are quite weak in Prisma, and their definitions fuzzy and because we were subsequently faced with an extreme heterogeneity of study designs and results that cannot be meta-analyzed.

What did the search produce?

The PubMed search yielded 316 papers as of the 11th of July, 2015. The search of the reference lists of these papers produced further 40 potentially interesting papers. Of the total output of 356 papers, 100 were completely unfocused and were captured for the presence of spandrels in the search strategy (however, we chose not to modify the strategy by adopting a more specific approach, since this would result in a potential loss of otherwise eligible material), 98 were excluded because they were reviews or meta-analyses, 16 because they were opinion papers-editorials or speculative with no experimental data, 55 were animal studies, 5 were case studies or case series, 7 did not include patients with bipolar disorder separately or did not investigate neuroinflammation at all, 50 were investigations of peripheral markers, 1 was a duplicate, and 4 were carried-out in vitro on human glial cells. The flow diagram in Figure 1 shows the search strategies and papers selected for review according to a modified Prisma algorithm. A total final number of 20 papers were found to be eligible and were analyzed. The search output spanned from 1982 to 2015; recalling that the first occurrence in PubMed of the term neuroinflammatory was in 1983, that of neuroinflammation was in 1995, and that microglial activation and related terms appeared during 1973-75, we may presume that there was a dearth of focused papers in the first years, i.e. prior to 2000. However, one of the includible papers was dated 1997. This was the case (19 papers up to 1999 and 337 from 2000 on) and the trend is one of increase through the years, witnessing an increasing interest of the scientific community in the neuroinflammation issue in psychiatric disorders in general, and in bipolar disorder in particular. Of interest, 2 of the included papers were not identified by the PubMed search despite the strategy was appropriate for singling them out. The included papers are shown in Tables 1 and 2. They fell into two broad categories, post-mortem (n = 15) and in vivo (n = 5), the latter comprising 4 studies of neuroinflammatory mediators in the CSF and one was an ingenuous positron emission tomography (PET) study of the binding of a neuroinflammatory marker in the brain. The only study we excluded as a duplicate was Rolstad et al.[21] which focused on the correlation between CSF neuroinflammatory markers and cognitive performance and admittedly reported data previously reported in Jakobsson et al.,[18] despite differences in sample size.

Figure 1. Results for search and inclusion and design typology (*Despite the existence of overlapping samples, most studies except one, were not considered duplicates since they reported on different datasets)

Postmortem studies included in this review investigating microglia or neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder

| Study | Origin | Source | Population | Measure(s) | Results | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ishizuka et al.[22] | Japan (Kumamoto, Fukuoka, Kyushu-Maidashi) | Kumamoto University, Department of Anatomy (postmortem autopsies); Neurosurgery School of Medicine, Fukuoka (brain sampling during brain surgery) | 11 neuropsychiatric patients, 1 bipolar; 2 surgical (brain sampled during neurosurgery for brain tumor) | Northern blotimmunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization to assess expression and distribution of MIP 1a/LD78 in brain | Increased expression of MIP 1a/LD78 in the bipolar patient in white matter glial cells | Evidence for increased expression of inflammatory marker in glia in the brain of just one patient with bipolar disorder; four patients with schizophrenia showed neuronal as well as glial distribution abnormalities |

| Hamidi et al.[23] | USA (Washington University, St. Louis, Mo; NIMH, Bethesda, Md) | Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center | 9 bipolar versus 8 major depression versus 10 nonpsychiatric controls | Microglial density (cells/mm3) in the amygdala | No differences between bipolar disorder and controls | Patients with bipolar disorder had been exposed to valproate or lithium more often than patients with major depression; higher suicide rates in patients versus controls |

| Frank et al.[24] | Germany (Mannheim, Heidelberg, Oberschleissheim) | Stanley Foundation Brain Collection, Bethesda | 3 bipolar, 4 schizophrenia, 4 nonpsychiatric controls for comparing retroviral RNA in various brain areas; 35 bipolar, 35 schizophrenia, 35 nonpsychiatric controls for all analyses in BA 46 (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) | Microarray-based analysis of HERV transcriptional activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. DNA chip investigated through Env-specific QRT-PCR. An animal retrovirus-specific microarray was performed to test the hypothesis of zoonosis | HML-2 family (HERV-K10) significantly overrepresented in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, compared to control brains. HERV E4-1 transcription overrepresented in bipolar disorder Env expression of HERV-W, HERV-FRD, and HML unaffected regardless of the clinical picture. No transcripts of any animal retroviruses detected with pet chip in all 105 human brains | HERV transcription in brain weakly correlates with schizophrenia and related disorders, but may be affected by individual genetic background, brain-infiltrating immune cells, or medical treatment; the higher incidence of HERV-K10 transcripts in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder is a probable consequence of high brain immune reactivity |

| Dean et al.[25] | Australia (University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC) | Autopsied cases at Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine | 8 bipolar versus 20 schizophrenia versus 20 nonpsychiatric controls | Prefrontal S100β levels (indirect evidence; astrocyte S100β and microglial IL-1β induce one another) | Decreased BA 9 and increased BA 40 S100β levels in bipolar disorder I versus other groups | Postmortem interval arbitrarily defined in not witnessed deaths; no suicide |

| Foster et al.[26] | England (King’s-Maudsley), Canada (University of British Columbia, Vancouver), Norway (Ullevål University, Oslo) and USA (UCSD, San Diego, CA) | Stanley Foundation Brain Collection | 15 bipolar, 15 schizophrenia, 15 major depression, and 15 nonpsychiatric controls | Double immune-fluorescence for the neuroinflammation marker calprotectin and microglia in BA 9 (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) | Higher levels in schizophrenia, lowest in controls, intermediate in major depression, and bipolar disorder in dorsolateral prefrontal microglia | Evidence of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder, but not so strong as in schizophrenia; post-mortem interval, age, and sex distribution not reported, but said to have not influenced results |

| Weis et al.[27] | USA (Bethesda, Md), Austria (Linz, Oberösterreich) and Switzerland (University of Zürich) | Stanley Neuropathology Consortium Collection | 15 bipolar, 15 schizophrenia, 15 major depression, and 15 nonpsychiatric controls | Immunohistochemistry to detect PrPc-positive cells in the cingulate gyrus | In the bipolar group, neuroleptics decreased the numerical density of PrPc-positive neurons and increased that of PrPc-positive white matter microglia | This is a very indirect measure of neuroinflammation, pointing to the possibility that drug treatment has something to do with it. Causes of death not provided |

| Rao et al.[28] | USA (NIH, Bethesda, Md and North Carolina) | Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA) | 10 bipolar, 10 nonpsychiatric controls | Western blot, total RNA isolation-real time reverse transcriptase PCR and immunohistochemistry of frontal cortex membrane, nuclear, and cytoplasmic extracts | Higher protein and mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-1 receptor, MyD88, NF-κB subunits, and astroglial and microglial markers GFAP, iNOS, c-fos and CD11b in the frontal cortex of patients with bipolar disorder | Excitotoxic markers were also up-regulated; the authors speculated that glutamatergic derangement (as shown by decreased protein and mRNA for NMDA receptors NR-1 and NR-3A) could be responsible for neuroinflammation |

| Kim et al.[29] | USA (NIH, Bethesda, Md) | Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA) | 10 bipolar, 10 nonpsychiatric controls (same sample as Rao et al.[28]) | Western blot, total RNA isolation-real time reverse transcriptase PCR and immunohistochemistry of frontal cortex membrane, nuclear, and cytoplasmic extracts | Increased protein and mRNA of AA-selective cPLA2 IVA, secretory sPLA2-IIA, COX-2 and mPGES in bipolar disorder; decreased COX-1 and cPGES compared to control brains | Deranged neuroinflammatory response, which the authors relate to excitotoxicity; tendency to repeat the conclusions of the preceding paper (Rao et al.[28]). The arachidonic cascade is not only involved in neuroinflammation but in other processes as well |

| Steiner et al.[30] | Germany (University of Magdeburg) | Magdeburg brain bank (D) | 12 suicide victims (5 bipolar, 7 major depression) versus 10 nonpsychiatric controls | Immunohistochemistry for the NMDA agonist quinolinic acid in the microglia of the anterior cingulate gyrus | Increased quinolinic acid-staining cells in the anterior midcingulatecortex and the subgenual, but not in the pregenual cortex, in the major depression, but not bipolar disorder, suicide victims | Drug treatment may have affected quinolinic acid content of microglia (thus masking a possible difference from controls in bipolar disorder); admittedly, microglial immunoreactivity may not be attributed to increased synthesis or decreased metabolic breakdown; relevance to neuroinflammation only indirect |

| Rao et al.[31] | USA (NIH, Bethesda, Md) | Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA) | 10 bipolar, 10 nonpsychiatric controls (same sample as Rao et al.[28]), matched; 10 Alzheimer’s disease, 10 nonpsychiatric controls, matched | Genomic DNA isolation, gene-specific and global DNA methylation; total RNA isolation-real time reverse transcriptase PCR for BDNF, NF-κB p50 and NF-κB p65, and global histone acetylation and phosphorylation, all from BA 9 (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) | Increased mRNA and protein levels of neuroinflammatory markers (IL-1β and TNF-α) and of markers of astrocytic and microglial activation in both bipolar and Alzheimer | Data compatible with altered frontal cortex epigenetic regulation related to neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder |

| Dean et al.[32] | Australia (University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC) | Victorian Brain Bank Network, Mental Health Research Institute, Parkville, Australia | 10 bipolar, 10 major depression, 19 schizophrenia, 30 age- and gender-matched nonpsychiatric controls | Western blotting and PCR for IL-1β and TNF-related measures in the prefrontal cortex and in the anterior cingulate | Transmembrane, but not soluble TNF-α transcript increases are found in the cingulate (BA 24), but not prefrontal cortex (BA 46); other groups did not show such increases; soluble TNF-α and IL-1β levels did not differ from controls in any mental group; decreased TNFR2 levels in bipolar disorder in BA 46; results not consistent with neuroinflammation | Significantly more patients with bipolar disorder had committed suicide compared to the other groups |

| Gos et al.[33] | Germany (Magdeburg and Leipzig) and Poland (Gdańsk) | Magdeburg brain bank (D) | 8 bipolar versus 9 major depression versus 13 nonpsychiatric controls | Hippocampal S100β levels (indirect evidence; astrocyte S100β and microglial interleukin-1 β induce one another)* | Numerical density of S100β immuno-positive astrocytes bilaterally decreased in CA1 pyramidal layer in both major depression and bipolar brains compared to controls; decreased density of S100β immuno-positive oligodendrocytes in left alveus only in bipolar disorder | No suicide among bipolar disorder patients, but 7 suicides among major depression patients; no evidence of neuroinflammation |

| Hercher et al.[34] | Canada (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC) | Stanley Medical Research Institute’s brain collection | 20 bipolar versus 20 schizophrenia versus 20 nonpsychiatric controls | Prefrontal microglial clustering coefficient and prefrontal microglial density (cells/mm2) | Not different from controls and patients with schizophrenia | Bipolar patients had committed suicide more often than controls and had more often a heavy drug abuse history |

| Fillman et al.[35] | Australia (Sydney, NSW, Australia) and USA (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pa and Stanley Medical Research Institute, Rockville, Md) | Stanley Medical Research Institute (Array Cohort) | 34 bipolar, 35 schizophrenia, 35 nonpsychiatriccontrols | Sample dichotomized to high- (n = 32) and low- (n = 68) inflammation/stress clusters according to differences in inflammatory and stress-related gene transcripts of RNA extracted from the frontal cortex and assessed through microarray analysis and PCR | Trend for bipolar patients to belong to the high inflammation/ stress group (n = 11), while patients with schizophrenia were significantly more likely than controls (n = 15 vs. 6) | 15 suicides among bipolar, 7 suicides among patients with schizophrenia; results partly support neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder |

| de Baumont et al.[36] | Brazil (São Paulo, SP and Porto Allegre, Rio Grande do Sul) and Portugal (Braga and Guimarães, Braga) | Stanley Neuropathology Consortium | 29 bipolar, 29 schizophrenia, 30 nonpsychiatriccontrols | RNA extracted from frontal cortex to assess gene expression profile; cloned DNA for microarray analysis | Immune response-and stress-related genes were differentially expressed between the control and the patient group; bipolar patients differed from those with schizophrenia in that the former showed an up-regulation of a set of 28 genes in bipolar disorder with respect to schizophrenia | Neuroinflammatory microglia activation is compatible with these data; the influence of medication has not been ruled out |

Studies in living humans included in this review investigating microglia or neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder

| Study | Origin | Population | Design | Results | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soderlund et al.[40] | Sweden (Stockholm-Linköping-Göteborg) | 15 bipolar I, 15 bipolar II, all euthymic, 30 healthy volunteers | CSF cytokine concentrations assessed through immunoassay-based protein array multiplex system; cross-sectional | Higher IL-1β and lower IL-6 levels bipolar than controls. Patients with recent manic/hypomanic episodes had significantly higher IL-1β levels than those without | Evidence for neuroinflammation and for IL-1β involvement; cross-sectional design is a methodological weakness |

| Stich et al.[41] | Germany (Freiburg, Greifswald) | 40 bipolar versus 26 controls with pseudotumor cerebri | Paired CSF and serum samples analyzed through ELISA to detect the concentration of antibodies against Toxoplasma gondii, HSV types 1 and 2, CMV, and EBV. Specific AI > 1.4 = intrathecal specific antibody synthesis; oligoclonal bands = chronic neuroinflammation | Eight patients with bipolar disorder versus 1 control had AI > 1.4; 5 patients versus 0 controls had oligoclonal bands | Cross-sectional design; possible that some bipolar patients have autoimmune disorder; 1 of 5 patients with bipolar disorder show evidence of neuroinflammation |

| Isgren et al.[42] | Sweden (Göteborg-Stockholm; England [London]) | 21 euthymic bipolar disorder patients versus 71 age- and sex-matched healthy controls | Measurements of serum and CSF concentrations of 11 cytokines; IL-6 measured through singleplex assay; IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-8/CXCL8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, TNF-α, and IFN-γ through the MSD 96-well multi-array and multi-spot human cytokine assay; validation of IL-8 measurement re-analysis: 21 patients and 20 controls with Proseek Multiplex Inflammation I | CSF IL-8 only was higher in bipolar patients with respect to controls; validation reanalysis showed measurements to have been valid, but also showed no correlation between serum and CSF levels | Cross-sectional design is a limitation. The study favors the presence of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder, but do not rule out that medication could account for the results; there was no correlation between central and peripheral data |

| Jakobsson et al.[18] | Sweden (Göteborg-Stockholm; England [London]) | 221 bipolar versus 112 healthy controls for serum sampling; 125 bipolar versus 87 controls for CSF sampling | MCP-1, YKL-40, sCD14, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 measured through ELISAs | MCP-1, YKL-40, and TIMP-2 levels higher in patients with bipolar disorder than controls in CSF; serum and CSF MCP-1, YKL-40 levels correlated, but differences in CSF levels between bipolar patients and controls were independent from serum levels | Cross-sectional design is a limitation. The study favors the presence of peripheral chronic inflammation and neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder, but also stresses the fact that the two are independent |

| Haarman et al.[43] | The Netherlands (Groningen) | 14 bipolar I versus 11 healthy controls | Dynamic 60-min PET scan after injecting [11C]-(R)-PK11195, a ligand of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor that constitutes a microglial marker | Significantly increased of [11C]-(R)-PK11195 binding potential in bipolar patients versus controls in the right hippocampus; a trend toward the same finding was present for the left hippocampus | This study provides strong evidence for the presence of neuroinflammation in bipolar I disorder, but the sample was small. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of the design does not allow to establish causality |

Based on the search, is there any evidence for neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder?

This review attempted to answer the question of whether neuroinflammation plays a role in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder.

We may not speak of conclusive evidence of neuroinflammatory mechanisms in bipolar disorder when the obtained evidence is too indirect. For example, when a molecule like N-acetylcysteine is found to have some therapeutic activity in bipolar disorder, we may not specify whether this is related to its anti-neuroinflammatory, anti-apoptotic stress, or antiapoptotic effect or to its mitochondrial dysfunction countering or glutamate/dopamine balancing actions,[44] unless accompanied by evidence of neuroinflammatory markers moving in the desired direction (and the demonstration of their alteration at baseline). Furthermore, the evidence of abnormal peripheral inflammatory reactivity cannot be taken as evidence of neuroinflammation.

Our search yielded a high number of interesting articles, but few of them suited the purpose of this review. This was due to the fact that our search strategy was over-inclusive to avoid missing any suitable article. It proved to be more tiresome to download all papers, but this allowed us to identify two papers that would otherwise have gone undetected. Surprisingly, the majority of suitable articles regarded postmortem studies. These studies (n = 15) [Table 1] favoured the idea of the existence of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder in their majority. Two provided indirect evidence for microglial activation, while four were not consistent with the presence of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder. However, in one of these,[23] it is possible that treatment could have set-off neuroinflammation. In fact, patients were receiving drugs like lithium and valproate, which both interfere with the arachidonic acid cascade,[45] one of the cross-roads of excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation.[46] The evidence stemming from in vivo studies (n = 5) is consistent with the presence of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder, also in consideration of the fact that most patients were sampled/tested when euthymic. The demonstration of peripheral benzodiazepine receptor alterations in bipolar I disorder patients may constitute a definitive demonstration,[43] but it should also be considered that such alterations in the brain of people with bipolar disorder, which are consistent with microglial activation, may not be specifically related to the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder or any diagnosis, but rather to disease activity.[47]

Causality effects, that is, whether it is bipolar disorder that once established triggers neuroinflammation, either through the adoption of a reckless lifestyle that is likely to promote a metabolic syndrome that facilitates the onset of neuroinflammation, or rather it is neuroinflammation, that has always existed in a given individual, that eventually ensued in bipolar behaviour and disorder, cannot be probed. In fact, to demonstrate causality we need longitudinal study designs, and in the case of neuroinflammation and bipolar disorder all relevant articles were based on cross-sectional articles. While this was mandatory for post-mortem studies, it was not for studies investigating living humans. Future studies should be able to tackle the causality question by studying the same patients across the various phases of their illness. However, the fact that the supposed neuroinflammation was present to some extent also when bipolar disorder was in its euthymic phases strongly argues against the lack of involvement of the brain immune system in bipolar disorder.

The studies included in our review were methodologically different and their sample sizes were much variable. Investigations of neuroinflammatory markers in the CSF were all but one carried-out in Sweden and conducted by the same Karolinska-Gothenburg group. One of these studies had to be excluded due to sample and data duplication,[21] but all these studies were quite consistent in their conclusions, supporting the existence of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder. This might have introduced a site bias. The markers tested each time in post-mortem studies differed, even when the same research groups were involved. Hence we had no population overlap, with the same group first reporting on some people and then on a bigger sample that comprised the formerly reported cases. We found no duplicates even when data referred to the same population in post-mortem studies. There was a tendency in Bethesda-based groups to support neuroinflammation while the German groups were more skeptical about it [Table 1].

Despite our care to avoid studies of peripheral immunity in bipolar disorder, many of these studies appeared through our search. This was due to the fact that many of these papers speak about neuroinflammation without actually showing it. In many of these fascinating and fashionable papers, the question of how chronic inflammation and immune derangement would "enter" the brain and produce neuroinflammation is much talked-about, but not proved. Another striking result of our search is the high number of reviews (n = 96), and especially of those focusing on this issue (n = 40). Most reviews mix-up peripheral and brain studies, reaching unwarranted conclusions. The activation of microglia must not be taken only as evidence of neuroinflammation, because it might also be consistent with a host of other functions, like remolding the brain microstructure, contributing to plasticity and synaptic formation, and responses to environmental challenges.[48] So it is possible that neuroglial activation, and precisely aberrant neuroglial function, may be responsible for some neuronal miswiring that is consistent with some psychotic symptoms that are frequently observed in bipolar disorder.

Summarizing, the evidence for the existence of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder is more yes than no. However, the hypothesis of a pre-existing peripheral inflammation passing in the brain and establishing a disease mode function, thus maintaining the disorder, is a mere supposition that is not based on evidence. Whereas neuroinflammation might lead to bipolar symptoms, it is not always true that neuroinflammation causes bipolar disorder, and it might be that only rarely is so. It is more likely that stress interacts with personal constitution and epigenetic factors to cause both neuroimmune dysreactivity and bipolar disorder in susceptible individuals. As de Baumont et al.[36] stated, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder may "arise from shared genetic factors, but that the resulting clinical phenotype is modulated by additional alterations mediated by microglia, possibly caused by interference of environmental factors at different times during neurodevelopment and early life, and/or epistatic interactions among groups of genes and environment". All this should be borne in mind when projecting investigations to explore the relationship between neuroinflammation and bipolar disorder.

Conclusion

This review attempted to answer the question of whether neuroinflammation plays a role in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Direct and indirect evidence points to some degree of possibility that this is the case, but studies heretofore are much heterogeneous in their methodology and conclusions, thus suggesting caution. It appears that the topic of neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder is a much under-investigated but over debated and highly reviewed issue. Finally, PubMed should be trusted, but alternative search engines should be used, lest precious articles are lost.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ms. Mimma Ariano, Ms. Ales Casciaro, Ms. Teresa Prioreschi, and Ms. Susanna Rospo, Librarians of the Sant’Andrea Hospital, School of Medicine and Psychology, Sapienza University, Rome, for rendering precious bibliographic material accessible, as well as their Secretary Ms. Lucilla Martinelli for her assistance during the writing of the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed(DSM-IV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

2. Akiskal HS, Pinto O. The evolving bipolar spectrum. Prototypes I, II, III, and IV. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999;22:517-34, vii.

3. Griesinger W. (Herausgeber). Über Irrenanstalten und deren Weiter‑Entwicklung in Deutschland. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 1868;1:8-43. (In German)

4. Smith DJ, Harrison N, Muir W, Blackwood DH. The high prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorders in young adults with recurrent depression: toward an innovative diagnostic framework. J Affect Disord 2005;84:167-78.

5. Guillaume S, Jaussent I, Jollant F, Rihmer Z, Malafosse A, Courtet P. Suicide attempt characteristics may orientate toward a bipolar disorder in attempters with recurrent depression. J Affect Disord 2010;122:53-9.

6. Mosolov S, Ushkalova A, Kostukova E, Shafarenko A, Alfimov P, Kostyukova A, Angst J. Bipolar II disorder in patients with a current diagnosis of recurrent depression. Bipolar Disord 2014;16:389-99.

7. Binder EB, Nemeroff CB. The CRF system, stress, depression and anxiety-insights from human genetic studies. Mol Psychiatry 2010;15:574-88.

8. McEwen BS. The neurobiology of stress: from serendipity to clinical relevance. Brain Res 2000;886:172-89.

9. Fricchione G, Daly R, Rogers MP, Stefano GB. Neuroimmunologic influences in neuropsychiatric and psychophysiologic disorders. ActaPharmacol Sin 2001;22:577-87.

10. Trowbridge HO, Emling RC, Fornatora M. Inflammation: A Review of the Process. 5th edition. Hanover Park (IL): Quintessence Publishing; 1997.

12. Selye H. Thymus and adrenals in the response of the organism to injuries and intoxications. Br J Exp Pathol 1936;17:234-48.

13. Cannon WB. The Wisdom of the Body. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, Inc.; 1932.

14. Brietzke E, Stertz L, Fernandes BS, Kauer-Sant'anna M, Mascarenhas M, Escosteguy Vargas A, Chies JA, Kapczinski F. Comparison of cytokine levels in depressed, manic and euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2009;116:214-7.

15. Gibney SM, Drexhage HA. Evidence for a dysregulated immune system in the etiology of psychiatric disorders. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2013;8:900-20.

16. Grippo AJ, Scotti M-AL. Stress and neuroinflammation. In: Halaris A, Leonard BE, editors. Inflammation in Psychiatry. Modern Trends in Pharmacopsychiatry. Basel (CH): S. Karger; 2013. pp. 20-32.

17. Schmitz G, Leuthauser-Jaschinski K, Orsó E. Are circulating monocytes as microglia orthologues appropriate biomarker targets for neuronal diseases? Cent NervSyst Agents Med Chem 2009;9:307-30.

18. Jakobsson J, Bjerke M, Sahebi S, Isgren A, Ekman CJ, Sellgren C, Olsson B, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Palsson E, Landen M. Monocyte and microglial activation in patients with mood-stabilized bipolar disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015;40:250-8.

19. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700.

20. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010;8:336-41.

21. Rolstad S, Jakobsson J, Sellgren C, Isgren A, Ekman CJ, Bjerke M, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Palsson E, Landen M. CSF neuroinflammatory biomarkers in bipolar disorder are associated with cognitive impairment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2015;25:1091-8.

22. Ishizuka K, Igata-Yi R, Kimura T, Hieshima K, Kukita T, Kin Y, Misumi Y, Yamamoto M, Nomiyama H, Miura R, Takamatsu J, Katsuragi S, Miyakawa T. Expression and distribution of CC chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha/LD78 in the human brain. Neuroreport 1997;8:1215-8.

23. Hamidi M, Drevets WC, Price JL. Glial reduction in amygdala in major depressive disorder is due to oligodendrocytes. Biol Psychiatry 2004;55:563-9.

24. Frank O, Giehl M, Zheng C, Hehlmann R, Leib-Mosch C, Seifarth W. Human endogenous retrovirus expression profiles in samples from brains of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. J Virol 2005;79:10890-901.

25. Dean B, Gray L, Scarr E. Regionally specific changes in levels of cortical S100beta in bipolar 1 disorder but not schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40:217-24.

26. Foster R, Kandanearatchi A, Beasley C, Williams B, Khan N, Fagerhol MK, Everall IP. Calprotectin in microglia from frontal cortex is up-regulated in schizophrenia: evidence for an inflammatory process? Eur J Neurosci 2006;24:3561-6.

27. Weis S, Haybaeck J, Dulay JR, Llenos IC. Expression of cellular prion protein (PrP(c)) in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. J Neural Transm 2008;115:761-71.

28. Rao JS, Harry GJ, Rapoport SI, Kim HW. Increased excitotoxicity and neuroinflammatory markers in postmortem frontal cortex from bipolar disorder patients. Mol Psychiatry 2010;15:384-92.

29. Kim HW, Rapoport SI, Rao JS. Altered arachidonic acid cascade enzymes in postmortem brain from bipolar disorder patients. Mol Psychiatry 2011;16:419-28.

30. Steiner J, Walter M, Gos T, Guillemin GJ, Bernstein HG, Sarnyai Z, Mawrin C, Brisch R, Bielau H, Meyer zuSchwabedissen L, Bogerts B, Myint AM. Severe depression is associated with increased microglial quinolinic acid in subregions of the anterior cingulate gyrus: evidence for an immune-modulated glutamatergic neurotransmission? J Neuroinflammation 2011;8:94.

31. Rao JS, Keleshian VL, Klein S, Rapoport SI. Epigenetic modifications in frontal cortex from Alzheimer's disease and bipolar disorder patients. Transl Psychiatry 2012;2:e132.

32. Dean B, Gibbons AS, Tawadros N, Brooks L, Everall IP, Scarr E. Different changes in cortical tumor necrosis factor-alpha-related pathways in schizophrenia and mood disorders. Mol Psychiatry 2013;18:767-73.

33. Gos T, Schroeter ML, Lessel W, Bernstein HG, Dobrowolny H, Schiltz K, Bogerts B, Steiner J. S100B-immunopositive astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in the hippocampus are differentially afflicted in unipolar and bipolar depression: a postmortem study. J Psychiatr Res 2013;47:1694-9.

34. Hercher C, Chopra V, Beasley CL. Evidence for morphological alterations in prefrontal white matter glia in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2014;39:376-85.

35. Fillman SG, Sinclair D, Fung SJ, Webster MJ, Shannon Weickert C. Markers of inflammation and stress distinguish subsets of individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2014;4:e365.

36. de Baumont A, Maschietto M, Lima L, Carraro DM, Olivieri EH, Fiorini A, Barreta LA, Palha JA, Belmonte-de-Abreu P, Moreira Filho CA, Brentani H. Innate immune response is differentially dysregulated between bipolar disease and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2015;161:215-21.

37. Liu L, Li Y, Van Eldik LJ, Griffin WS, Barger SW. S100B-induced microglial and neuronal IL-1 expression is mediated by cell type-specific transcription factors. J Neurochem 2005;92:546-53.

38. Griffin WS. Inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:470S-4S.

39. Griffin WS, Stanley LC, Ling C, White L, MacLeod V, Perrot LJ, White CL, 3rd, Araoz C. Brain interleukin 1 and S-100 immunoreactivity are elevated in Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989;86:7611-5.

40. Soderlund J, Olsson SK, Samuelsson M, Walther-Jallow L, Johansson C, Erhardt S, Landen M, Engberg G. Elevation of cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-1ss in bipolar disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2011;36:114-8.

41. Stich O, Andres TA, Gross CM, Gerber SI, Rauer S, Langosch JM. An observational study of inflammation in the central nervous system in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2015;17:291-302.

42. Isgren A, Jakobsson J, Palsson E, Ekman CJ, Johansson AG, Sellgren C, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Landen M. Increased cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-8 in bipolar disorder patients associated with lithium and antipsychotic treatment. Brain Behav Immun 2015;43:198-204.

43. Haarman BC, Riemersma-Van der Lek RF, de Groot JC, Ruhe HG, Klein HC, Zandstra TE, Burger H, Schoevers RA, de Vries EF, Drexhage HA, Nolen WA, Doorduin J. Neuroinflammation in bipolar disorder - A [(11)C]-(R)-PK11195 positron emission tomography study. Brain Behav Immun 2014;40:219-25.

44. Deepmala, Slattery J, Kumar N, Delhey L, Berk M, Dean O, Spielholz C, Frye R. Clinical trials of N-acetylcysteine in psychiatry and neurology: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015;55:294-321.

45. Duncan RE, Bazinet RP. Brain arachidonic acid uptake and turnover: implications for signaling and bipolar disorder. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2010;13:130-8.

46. Rapoport SI. Brain arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid cascades are selectively altered by drugs, diet and disease. Prostaglandins LeukotEssent Fatty Acids 2008;79:153-6.

47. Cagnin A, Kassiou M, Meikle SR, Banati RB. Positron emission tomography imaging of neuroinflammation. Neurotherapeutics 2007;4:443-52.

Cite This Article

Export citation file: BibTeX | RIS

OAE Style

Kotzalidis GD, Ambrosi E, Simonetti A, Cuomo I, Casale AD, Caloro M, Savoja V, Rapinesi C. Neuroinflammation in bipolar disorders. Neurosciences 2015;2:252-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/2347-8659.167309

AMA Style

Kotzalidis GD, Ambrosi E, Simonetti A, Cuomo I, Casale AD, Caloro M, Savoja V, Rapinesi C. Neuroinflammation in bipolar disorders. Neuroimmunology and Neuroinflammation. 2015; 2: 252-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/2347-8659.167309

Chicago/Turabian Style

Kotzalidis, Georgios D., Elisa Ambrosi, Alessio Simonetti, Ilaria Cuomo, Antonio Del Casale, Matteo Caloro, Valeria Savoja, Chiara Rapinesi. 2015. "Neuroinflammation in bipolar disorders" Neuroimmunology and Neuroinflammation. 2: 252-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/2347-8659.167309

ACS Style

Kotzalidis, GD.; Ambrosi E.; Simonetti A.; Cuomo I.; Casale AD.; Caloro M.; Savoja V.; Rapinesi C. Neuroinflammation in bipolar disorders. Neurosciences. 2015, 2, 252-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/2347-8659.167309

About This Article

Special Issue

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Cite This Article 2 clicks

Cite This Article 2 clicks

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.